Unaltered lessons and advice in growing to Staff and Director levels at fast-growing companies. From Louie Bacaj.

Louie Bacaj has an impressive story. Coming from poverty, he put himself through college to become a software engineer, joined Jet.com as a senior engineer, and became the youngest Senior Director of Engineering at Walmart. He then quit his corporate career – waving goodbye to close to $1M/year in compensation – to become an entrepreneur.

I wanted to learn more from Louie after I purchased and watched his course Timeless Career Advice for Software Engineers. In only 90 minutes of video, Louie shares so many of his accumulated insights from over a decadeʼs worth of hard-earned experience – and does so with radical transparency.

This radical transparency is why I wanted to link up with Louie. He has no immediate plans to go back to working a corporate job, and I latched on to the opportunity to get his unfiltered story and advice on how he traveled a path which many software engineers hope they might do, one day.

I was not disappointed. I highly recommend both following Louie on Twitter where he shares much more unfiltered advice, and to buy his Timeless Career Advice for Software Engineers course, which is a bargain at $25, considering it not only comes with 90 minutes of video content, but also includes Louieʼs complete income progression guide, and another 4 bonus topics on how to ask for a raise, switching teams, switching disciplines and finding mentors.

In this issue, Louie shares his story and learnings via the following steps:

- From new grad engineer to senior software engineer �. From senior engineer to engineering manager

- Being an engineering manager

- From engineering manager to director

- From director to senior director

- Staff promotions advice from a senior director

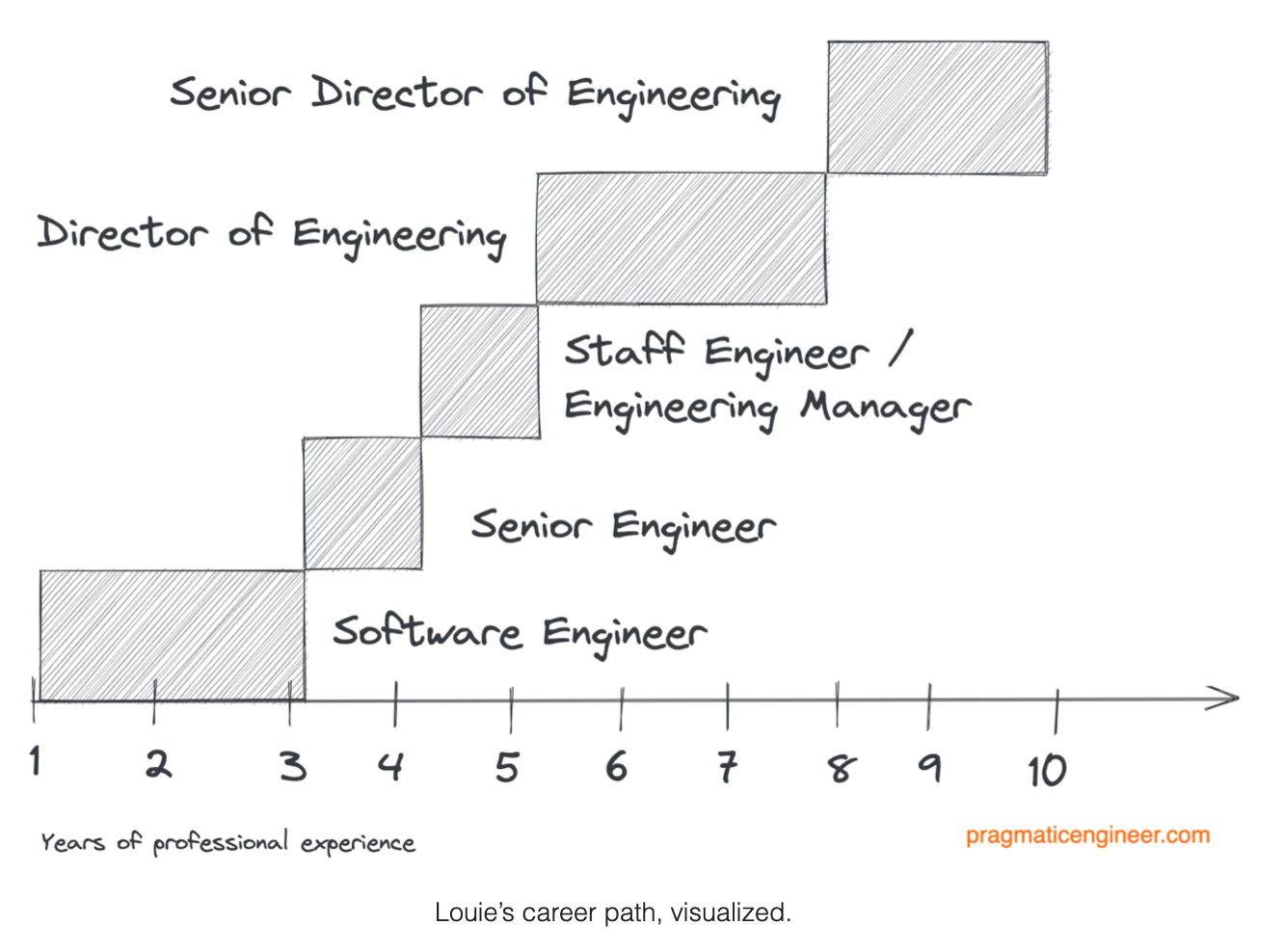

Louie’s career path, visualized.

Louie’s career path, visualized.

1. From New Grad Engineer to Senior Engineer

In 2010, I was putting myself through college, completing my Bachelorʼs. On the side, I built websites for businesses as side projects. I used HTML, CSS and some Javascript. I mostly built websites for restaurants. They were not for taking orders; they were just a basic storefront for displaying contact information and the menus.

These projects worked out well for both me and the restaurants. I needed to make some money on the side while I was studying and restaurants had very small budgets; not enough to hire an agency, but enough so I could build them a website.

After graduating, I got my first professional developer job. I worked for a company called SunGard. This firm was making software for big banks. Upon joining I got to see how these really big banks work from the inside. I was overwhelmed and had impostor syndrome. Thatʼs when I decided I should do a Masterʼs to combat my inferiority complex. I ended up doing a Masterʼs as a part-time program, while I worked full time at SunGard.

Too much knowledge is just like too much money. If youʼre only accumulating it, but not putting it to work, itʼs wasted effort. In hindsight, I never needed a Masterʼs degree as a software engineer. The Masterʼs gave me credentials, however I never felt I used the knowledge gained through that program.

While at SunGard, I realized we were doing the same work as the people working in the bank. We worked side by side with them, often on the same team. However, there was one big difference: the engineers at the bank were paid a lot more.

I decided that I should make more money, and the easiest way to do this was to be employed by a bank. So I got a job at Bank of America.

Initially, it felt really cool to work at a big bank. But the coolʼ feeling quickly faded. Six months in, I would go into meetings where leadership would brag about how we, the software engineers, will help eliminate hundreds of thousands of jobs through automation. This was when I started to feel jaded. I asked myself “why are we even doing this? Is this the type of software I want to be building?”

I started to realize I didnʼt want to be there, and slowly began to loathe my job. I started to interview around, looking through job ads on LinkedIn, and came across Jet.com. They offered me a job, but the problem was that it was a paycut from my job at the bank.

I was conflicted. The job seemed really interesting, because they were using brand new technology. They were jumping on Azure when Azure was brand new in 2014. They were still a company with only a couple of people in a warehouse in New Jersey. Should I join this place?

Jet.com was founded by Marc Lore. Marc sold Diapers.com to Amazon in 2010. He stayed there for two years, but he was unhappy with how things went. Frustrated, he quit Amazon and decided to build a better competitor. He raised funding for Jet.com and was hiring the initial team of engineers when we talked.

I ended up talking with a lot of people at Jet.com. I felt they were being honest with me, and I liked how the founder had done an exit before, and now he had the guts to try and take on Amazon. I was thinking, who does that?ʼ

The signals I gathered to decide whether join this startup were these:

- People. Who would I be working with?

- Mission. What are they doing? Is it exciting? Do I want to be a part of this?

- Technology. Which technology are they using? Would I learn something here? Am I excited about the technology?

- Capital. Do they have enough money to keep paying people?

- Business model. Is there a business model that makes sense and will generate enough revenue?

One thing that was a crazy decision was how Jet.com went all-in with Azure, which was new and less stable than AWS. Why? Because the founder, Marc, wanted to give no money to Amazon. They made the decision despite Azure being far more limited than AWS at the time. This decision would later make Jet.com one of the largest Azure customers.

Little did I know that later at Jet, we would be one of the biggest beta testers of new Azure features like Cosmos DB, change feed, TTL and others, with Jet going through a lot of pain in this process. The Azure team, at the same time, was very supportive. Still, it made for a real challenge; we were running effectively on beta software, in the real world. Our pagers went off frequently.

I liked everything about Jet.com, except for the salary cut I would have to take. In the end, I took the offer. It was a team I wanted to be a part of, so I made the jump.

2. From Senior Engineer to Engineering Manager

I joined Jet.com as engineer #20. I came in at the end of a large hiring spree in which about 15 engineers were hired. Beforehand, 4-5 engineers worked at the company.

The technology decisions were interesting. The core team could not decide whether to use C# or F# on the backend. So they built two MVPs: one with C#, one with F#. Then they chose F#.

I was surprised they would build things twice in a fast-moving startup. But thatʼs the thing about fast-moving startups. They always do things that surprise you, and things you can learn from.

I liked how they picked F# because this meant I could learn something new. Because F# was built on top of .NET, you could hack around or use other existing .NET libraries. I learned how to “hack” what I wanted to do until I could do it in a functional style.

By the time I joined Jet.com, I was a senior software engineer. And I had some leadership experience. At SunGard, I had project responsibilities; I was leading projects and doing all the work, except for managing people.

At Jet.com, they didnʼt care about my leadership experience. They needed doers, not managers. The company was building this amazing pricing technology. The idea was that they would scrape the market in realtime, and offer goods on Jet.com cheaper than anyone else was selling at.

I was working on pricing areas at the bank, so when I heard about this technology, I told the CTO he should put me on the pricing team. I told him I knew this area, I had lots of ideas, I was very interested, and I would make a large impact.

The CTO told me to forget about the pricing team because Marketing was struggling and had no developers. He told me I need to go in there, and help them.

Marketing was trying to get people to use Jet.com. But they had no tech support. They were struggling to send emails or run campaigns.

A learning at a startup is that you need to do what helps the company most, and not what you are most interested in doing. Jet did not need more people on the pricing team; it needed Marketing to start being productive. I said “yes” to the CTO and figured Iʼd learn about marketing while at it – an area I had no idea about. Iʼd get the job done and go back to Pricing afterwards.

When I arrived at Marketing, it was a mess. People were emailing Excel CSVs with customer emails, hacking around with tools, and doing everything ad hoc.

I looked around and decided this ad hoc way of working needed to stop. So I started to build databases to store customer information, integrated APIs to do things with one click that used to take hours of manual work and made the most common marketing tasks much faster and easier to perform.

Once this work was done, I went back to the CTO to tell him that Iʼd completed my work at Marketing, and I now wanted to get back to Pricing.

The CTO told me that Marketing was happy, but they wanted me to do more. They wanted personalized emails. They wanted a CRM. They wanted more granular tracking. At first, I was not excited to keep working in Marketing. But then I realized something that changed my perspective.

Jet took so much VC money that there were only two outcomes on the cards: either it grows like a rocket, or it crashes and burns. There was nothing in-between. And to grow like a rocket, they needed an amazing marketing team, with excellent tooling.

I then decided: “Okay, let me double down on this area. Even though I know nothing about marketing, and nothing about AdTech, Iʼll learn and do my best possible work.” And so I did.

Six months later I was overwhelmed. I had built so many features, and in between that I was supporting them, and kept needing to build more things. I told my CTO I was too stretched: I couldnʼt keep writing all this code, talking to all these vendors, and talking with all the marketing people and supporting all of them. One time, I was awoken in the middle of the night because one of the systems Iʼd built was down, and the next day I had an early meeting with a vendor I was integrating.

It was too much. I told my CTO and the EVP engineering that I needed more people to help with all the work because I could not keep up. I was told I could hire two engineers, which I did. Within a year, this team turned into a 10-person team and I was the manager.

3. Being an Engineering Manager

As I started growing a team and working in the Marketing department, I realized just how big the marketing world at Jet was. Our affiliate sales skyrocketed. We drove millions in sales with just a few changes.

I started to get interested in the business side of things. I started to read more about marketing, growth, affiliates and to dive deeper into this fascinating world. I learned about how other companies use marketing, and started to understand why they invest so much money to build in-house systems, as opposed to just buying ads.

One thing I learned as a manager is you should understand why you are valuable to the business. I was naturally curious about how things worked.

This curiosity later paid off, both in being able to know if my team was supporting the business the best we could, and also it helped us grow more, as every new hire meant more profits generated for the company.

The way I hired the first people was less glamorous than you might think. I was working crazy hard, and was overwhelmed. Finally, I got permission to hire a few people. I was thinking: “what should I hire for?” I was working really hard at the time and decided the first new hires needed to be people who could do the same; especially as I felt I wonʼt have time to help them.

However, as we did interviews I found myself trusting the judgment of other interviewers more than my own. This was mostly because I was so busy that recruitment was a low priority: keeping things running day-to-day was much more pressing.

My first hire was a guy who was based in Australia, who already knew F#. We ended up working together for a long time and we climbed the ladder together. He also became a director at Walmart. Onboarding him was a pain because for the first two months he was working remotely from Australia, while waiting on his visa. However, once he moved to New Jersey, we started to hire more people and the team grew.

On my first promotion I was double-bumped. I joined the company around March 2015 as a senior engineer. The first promotion cycle came in February of the next year. At the time, the levels at Jet went like this:

- Software engineer

- Software engineer 2

- Senior engineer (my level)

- Senior engineer 2

- Staff engineer

For common levels within Big Tech, see the article Engineering career paths at Big Tech and high-growth startups.

The company decided that managers should be at least at the same level as staff engineers, and so I was moved two levels up, officially becoming a staff engineer.

I had tons of support internally for my promotion. I was working around the clock at Marketing, sitting with them, understanding their problems then quickly building systems to solve those problems.

It was actually Marketing which was regularly pinging the CTO, telling him to both promote me and to get me more people as “heʼs doing such a great job but could do even more with more people.”

As my team grew rapidly, we started having trouble due to this. There are a few rules of thumb I had to learn the hard way during this phase. Rules like:

- Have a critical mass of people who know what they are doing. This means hiring enough people who have done something similar before. If you donʼt do this, you are in a world of pain. This is also the reason many startups hire senior engineers, not just early-career ones.

- Have almost enough people. If you have too few people, they are stretched and burn out. With too many people, thereʼs not enough meaningful work for everyone. When you have almost enough people, everyone is stretched to the ideal extent. It also means people work on the most important things.

- Donʼt grow all the time: stop growing, level set with everyone, then start growing again. Repeat this cycle, instead of continuously expanding the team. By stopping hiring every now and then, you can get the team to solidify, and for everyone to catch up and get to the same level.

- Nudge engineers to talk to the business. Whenever we had a new hire come in, they would eventually have questions about the business side of things. I could have answered these, but I didnʼt. I told them to go to the business folks and ask them directly. They did, and not only did they answer the question, but they started to ask more questions. With this approach, all my engineers became much more business- aware, and the business also trusted us more. Much of the success of my group was down to these connections forged between engineering and marketing.

These were the lessons that I got during our high growth phase. Other people will have other lessons. Youʼll learn these as you go. My advice is to pay attention to what works and why it does.

As a manager, you need to care about people to be successful. If you donʼt care about listening to people, hearing their problems, or care about where people will be a few years later in their career, then youʼll be a terrible manager.

Without empathy for people, youʼll also be viewed as the manager who is building their own empire and hiring people they donʼt care about as individuals. In most cases, Iʼve seen the story end badly for managers with this attitude; they had to leave, one way or the other.

4. From Engineering Manager to Director

As my team grew, we noticed an opportunity to split up into two groups. We realized we were working on two separate things:

- Retention: tools to retain customers on Jet.com. Personalized messages, discounts for retaining, predicting churn and a CRM to be able to contact customers at risk of churning.

- Acquisition: getting more new customers on the website. We built tools to experiment with Facebook and Google ads, and optimized to drive the most customers for the lowest cost.

At 15 people, the team got too big for me to manage. So I decided to split it up. But instead of dividing into the two obvious teams, I decided to plant the seed for a third team; a feature team that could help and add features to the main website. I noticed that a lot of the Marketing teamʼs asks were to do with changes on the Jet website, and they were going to the existing teams to ask for Marketing features. I realized this didnʼt work well, so I made a case for a Marketing Website team, so we could do this work directly.

I already identified two engineers who were good candidates to lead these teams. They were people who were already acting as leaders in their own domains.

The Marketing business was a strong supporter of the split, as they understood the value each team would provide. And after the split, it was easy to connect the business impact of each team to the systems they worked on, so we could get more funding.

What helped me grow into a manager of managers was how I understood the business and had a strong relationship with the business stakeholders. Because of this, we organized the team in a way that helped Marketing, and they understood exactly how we were moving the needle.

I eventually got the directorʼ title after a few promotions. Every promotion cycle, I would be promoted because both the impact of my group had increased and the business was strongly supporting my promotion case. My group was bringing in such good results that I didnʼt even have to ask for these promotions.

5. From Director to Senior Director

When Walmart acquired us, my team became part of Walmartʼs online pharmacy team. This was a unit with 100M customers and making $35B revenue per year. I was given an even bigger team than before, to manage 6 engineering teams with around 50 engineers in New Jersey, Bentonville and India. I also got the Senior Director title.

This was a huge shift, as both myself and my team had previously worked in marketing and AdTech. Pharmacy was a different level in terms of impact. Here, a mistake would not just cost money. If we inaccurately recorded a customerʼs prescription, we could put their life in danger.

Everything within Walmart Pharmacy was legacy, and our job was to modernize it. Most of the stack was built in the 1990s. And the way engineers built new things was interesting.

Every time the team would add a new feature, they would spin up a new system. They would manage all the infrastructure and security for this new system according to the USAʼs Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA.)

It took me some time to get my head around this situation, and then I laid down some ground rules. I observed that people were making wildly inconsistent decisions, and each system was different; a unique snowflake in its own right.

We started by laying down a few principles:

- Tools and frameworks people can use. In the past, this was down to the teams. We came up with a more narrow list.

- Central infrastructure. We opened up a cluster that was to be used for all new feature development; one which was easy to onboard to, and where the infrastructure was already built, with security and audit capabilities baked in.

My job became not only managing people, but also managing lots of consultants and an army of people who were supporting this organization. I felt it was my job to become a shield for my team. My job was to ensure that consultants and people outside my team did not derail us from seeing through the modernization of our engineering environment.

I had a lot of fights with people. Some days, I felt like my role was more about battling teams which did not report to me. My title helped; at big companies, people pay more attention to big titles.

As we pulled off great work, many of my engineers got promoted for what they achieved. One of the first things we built was the shared infrastructure which we called the HIPAA Cloud.ʼ It was one of the best projects that came out of Walmart Pharmacy. Many people on my team got promoted because of this project, including two engineers going from staff to principal.

Both these engineers were leading their part of the project and we had really good relationships. This female staff engineer – who was one of the people later promoted – would pull me aside and tell me they needed me to come into a meeting and convince person X or Y they needed to do something. So I would do just that, as I trusted them since theyʼd delivered so much already.

If I didn't have these people, it would've been really hard to achieve what we achieved. I wouldn't have been able to successfully challenge other teams and my own team. But when my folks roped me in, I knew right away what I had to do.

We had lots of pressure because of COVID. Walmart wanted to move fast and scale up how Pharmacy worked. Many of the consultants pushed us to get things done dirty, but me and my team pushed back to do it properly. We were no longer working at a scrappy startup, and we knew how mistakes were not acceptable, given we were in the business of delivering drugs to people. We also knew we would own the systems and would get woken up by pager alerts if things were built poorly.

If COVID had not happened, we would have had a much more peaceful building and modernization process of Walmart Pharmacy. Because of COVID and all the pressure, we had to shuffle people around. I hate shuffling people around, sending them to work on other teams. But we had little choice, so I asked for volunteers for projects that needed people immediately, and this worked out well enough.

My job as a Senior Director changed my work in many ways:

- Completely disconnected me from coding. I no longer wrote code, nor did I interact with it.

- Fully trusting people under me. As I had tons of meetings, I had to fully trust the people under me, that they are competent and would not drop the ball. And none of the people whom Iʼve worked with did that.

- Set the ground rules for everybody and make sure the rules are enforced.

- Ensure tactical things donʼt trip us up. I had to make sure that our short-term decisions would not trip us up, and had to keep a lookout for the long-term success of the group.

- More meetings, more negotiating. My number of meetings exploded. I was in so many discussions, from dealing with attrition, to swapping headcount, to securing budgets, to pushing back on projects we could not take on.

If you have a solid foundation of people who are competent, then itʼs really easy to keep building and expanding. People will then tell you when something is wrong, and they will not go in a direction they disagree with. In many ways, most of my success in my management career was based on this professionalism.ʼ

6. Staff Promotions: Advice from a Senior Director

As you move up, itʼs more about the people. When youʼre at a staff, principal or distinguished level, you need to be nice to people less experienced than yourself, and to be so even when they might be wrong. If you donʼt do this, youʼll build up a reputation as a jerk. Being nice to people and giving them space isnʼt just about not being a jerk. People need to get comfortable with devising their own ideas and making mistakes as they try new things, and to learn as they do.

For example, if an engineer comes to you and explains their architecture approach and you think itʼs flawed, you should not start by explaining what is wrong with the idea. Instead, have this person explain their thinking. Ask questions which will lead this person to figure out where the gaps are and ideally to come to the conclusion by themselves.

Get good at selling your ideas to others. People will not do what you say just because you tell them. You need to convince engineers about the viability of your ideas. This means listening to them, and involving them in discussions and decisions. If you try to force your ideas down othersʼ throat, it wonʼt work.

You need time to build the skill set of selling your ideas to others, so start practicing this early. A great way to grow this skill is to get exposure to a lot of different problems. By doing so, you build up both a breadth of understanding, and you start to piece together more things. By having a broader exposure, youʼll be able to both bring better arguments and come up with more and superior tradeoffs.

Get the business folks on your side, and turn them into your advocates. Do what I did with Jetʼs Marketing team. Understand what the business you support does, talk to people, then solve their pain points.

It's hard for tech leadership to ignore engineers who have the business advocate for them: telling leadership they are getting tons of value and want more from them. Understanding and supporting the business were the skills I tried hard to teach people on my team. It is a crazy underrated technique to grow fast, as an engineer.

The job drastically changes as you climb the ladder. This is an area most people donʼt realize; that your job changes very much as you get promoted, even as an individual contributor. Many people want to climb the ladder to get more money, and a fancier title. However, the nature of the job changes as you move up.

Individual contributors spend far less time coding at the higher levels. They start to do more teaching, selling, and participating in meetings. Many realize these changes too late. It's best to be very deliberate as you progress and do it with your eyes opened. Is the next position really one that you want? Are you okay with giving up more of the hands-on parts of the job for more abstract work, in exchange for somewhat higher compensation?

Read more about how responsibilities change on the individual contributor track in the article Engineering leadership skill set overlaps.

Your impact becomes important. To get promoted, you need to demonstrate impact. At many large companies, they value things like building a feature which lots of people use, or a tool that becomes adopted internally.

Be able to answer the questions of “what improved, is the company saving money, are engineers spending less time on repetitive tasks, did the user signup conversion improve? Once the company can answer those questions, then youʼll have a better grasp of your impact.

However, the reality is that itʼs hard to measure the impact of many things you build. But if you have a nice number that reflects pretty well the impact you made, will this get you promoted? Not necessarily.

Your manager has to fight for you to get that promotion. When managers go into the calibration meeting with your impact, guess who else will also have had an impact? A bunch of other engineers, thatʼs who. And there might be a budget for only one promotion. So now these other managers are fighting for their person to be promoted.

Managers making a strong case for their own people's promotions happens everywhere. I had mentors from FAANG, where it works the same way. This is all the more reason for good relationships in your org and across orgs. And also with other engineering managers and even with business folks for the support.

The higher up you are, the more you need to understand organizational politics. A lot of engineers who want to get to these higher levels are naive to the fact that politics becomes important. They think that just because the organization was founded by technical people, technical excellence is all that counts for career advancement.

In reality, technical excellence is just table stakes. Of course you need it to succeed – but you need all this other stuff, too.ʼ

Read more about promotion-driven development and how to avoid it in the article Preparing for promotions ahead of time.

Takeaways

Switching jobs earlier in your career can make a large difference to money and experience. Louie switched from a company working for banks, to working directly inside the bank. Not only did this change result in a much higher salary, but it gave him a different and fresh perspective. Louie did not job hop, he spent 3 years in his first job at SunGard and earned enough experience and trust to lead projects.

Joining a startup is a risk and no one can make this call but you. Going from a stable and well-paid job at Bank of America, Louie was offered less salary to work at a tiny startup with a charismatic founder. Louie used five signals to decide if heʼd take the gamble: people, mission, technology, capital and business model. I like his thinking, and strongly suggest asking questions about the business model and capital some learnings I also share in takeaways from Fastʼs rapid collapse.

In a fast-growing company, working closely with the business is an underrated way to make an impact. One of the things that made Louie stand out from his peers was how he spent a lot of time both understanding and helping the business. Instead of being obsessed with solving interesting engineering challenges only, Louie got obsessed with solving the challenges Marketing had. Marketing was then his biggest advocate in him becoming a manager, and later in growing his team.

To be a great manager, care about your people. This observation sounds clichéd, but it really is not. Talking with Louie, I felt he was someone who cared greatly about everyone on his team, and tried to pull people up with him. His earliest hires did very well career-wise, and Louie helping them and advocating for them surely contributed to that.

When leading more than 4-5 teams, your job becomes more abstract. When Louie got to the Senior Director position, he led an engineering group of ~50 engineers, and his job changed dramatically. His impact was made through others, and he was no longer anywhere close to the code.

While moving up the corporate ladder is valuable and profitable, there is more to professional growth than just the corporate ladder. This last observation came to me after talking with Louie. I reflected on how Louie gave up a promising and profitable corporate career to chase his dream of supporting himself by choosing entrepreneurship as his new career path. This transition is not common across engineering leadership, but I am noticing several people taking leaps into less explored career paths, following a successful corporate career.

I am not advising that leaving corporate should be the goal for most people.. However, I am suggesting that itʼs worth treating progress up the corporate ladder as not the destination, but as progression, change, and taking on challenges you have not taken on before.